Dimensions

Know the ledge

The usability of each obstacle in a skate park should be the top priority. The usability should help dictate the proper dimensions for each obstacle such as the height, width, depth, shape etc. Enough open space around each obstacle to allow for full usage should help dictate the layout.

In this article my goal is to demonstrate the application of a process I call a usability analysis. As my example obstacle I chose ledges. I measured the height, width, depth, run up and the available space to the side of each ledge at Flushing, Reggaeton, Chauncy and two boxes and one bench at Blue park. Give it a read to find out the results and conclusions drawn from this study.

Let’s start with Flushing. Generally amongst skaters the ledge over the grate at Flushing meadows is considered a high ledge. The ledge there is approximately 19 and 1/4 inches tall.

Because the ledge is a giant circle there is ample space for approaching this tall ledge but also because it is a circle there are no end points to the ledge. The depth of the ledge at flushing is 38 inches.

Each granite cap that makes up the flushing ledge is approximately 5 feet wide.

There are four granite caps above the grate. So the width of the grated section under the ledge is 20 feet. Despite the copious amount of run up space and somewhat accommodating depth, the fact that the ledge is 19 1/4 inches high and has no end points make flushing a relatively difficult ledge to skate. An advanced ledge skater these days can most likely do a fair amount of tricks over the grate and most of their other tricks on the waxed sections not over the grate. They could also learn a new trick on the ledge not over the grate and eventually do that trick over the grated section. An average ledge skater can probably do the two or three tricks they feel most comfortable with plus a noseslide and 50 50 over the grate and maybe half of their bag of ledge tricks on the ledges not over the grate. They would likely find it difficult to learn a new trick at Flushing. A smaller ledge would be needed and then that trick could be practiced on the non grate section and maybe eventually over the grate. A novice ledge skater maybe could noseslide or 50 50 over the grate and also do those tricks and a few more on the ledges not over the grate. While learning would be roughly the same process as an average skater but with a longer timeline. A person just starting out skating will find it impossible to do any trick on even the ledges not over the grate for quite some time.

Flushing meadows is a world famous skate spot and I enjoy skating there myself. However if one considers the range of skateboarders that will be using an obstacle (such as a ledge) in a skate park setting, basing dimensions off of this world famous skate spot would be a mistake.

So how could a skate park designer figure out what the most accommodating ledge dimensions would be for a wide range of skaters who will be using a potential skate park. Well Flushing isn’t the only ledge spot that exists. Maybe if we look at a variety of ledge spots that a range of skaters skate and compare their dimensions we can come up with some general guidelines.

The ledge spot at S5th and Rodney st in Brooklyn, NY (better known as Reggaeton) gets used by a range of skaters so let’s start there. For this study I’m going to focus solely on the lower basketball court which is where the low ledge against the fence is and across the court is what I’ll refer to as the regular ledge.

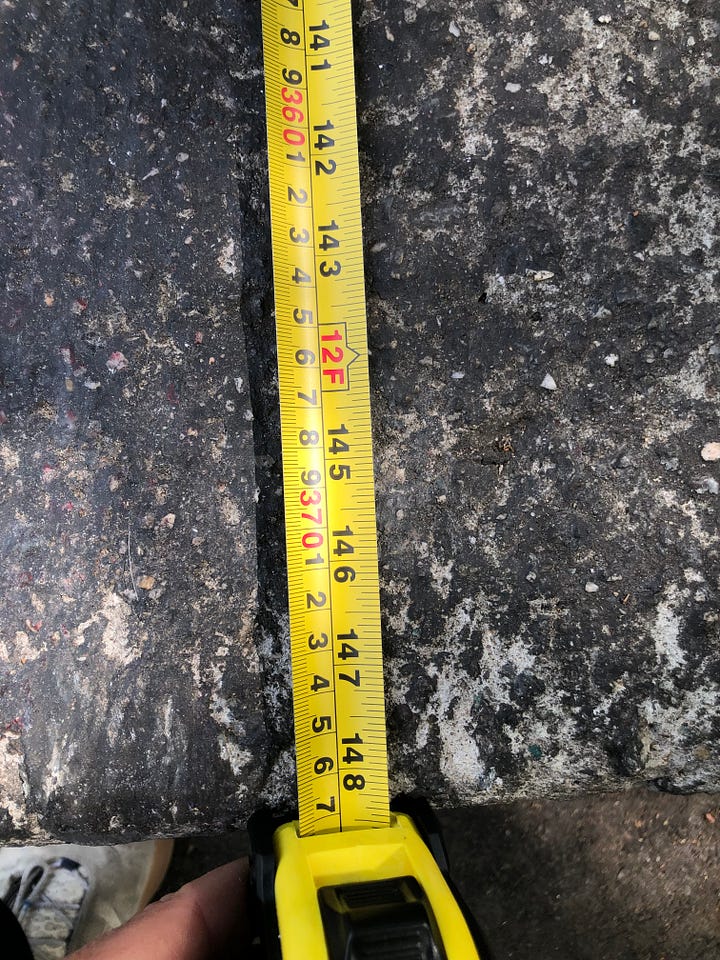

The height of the low fence ledge is 12 1/2 inches at its low point and 13 1/4 inches at its high point.

The waxed section of the low fence ledge is about 94 inches wide and the depth is roughly 8 inches.

These dimensions are polarizing to say the least. I’ve skated with a lot of people at Reggaeton and most people either love or hate the low fence ledge.

What people tend to love about the fence ledge is the fact that the 8 inch depth which is backed by a chainlink fence coupled with the relative low height of between 12 and 13 inches lends itself to learning or doing tech ledge tricks. It’s also good for beginners just learning to grind and slide a ledge. The chainlink fence provides a safety for overshooting trick attempts and the low height requires less energy and precision to fling tries and possibly still get on top of the ledge.

What people tend to hate about the low fence ledge is also the chainlink fence. The 8 inch depth is so shallow that the fence can catch your heels on backside grinds. Also the 94 inch width is a relatively short grind or slide. If you approach the ledge with a decent amount of speed you have to hop on and off the ledge quickly. Even going somewhat slow you still have to hop on and off fairly quick to avoid having your board or feet hit one of the vertical fence posts. And of course there is the dreaded dragging of one’s hand or fingers along the chainlink fence.

The approach to the low fence ledge from the step side is around 38 feet and from the back fence the run up space is about 43 feet. When I skate reggaetone I feel like this isn’t quite enough run up. However I enjoy enough of the other attributes of reggaetone’s layout and dimensions that I still skate there often. I think the general consensus is that this amount of approach space is a bit too short. You get about one push or a throw down and then have to somewhat quickly set up.

There is plenty of space to the side of the low fence ledge due to the fact that it’s on the perimeter of a basketball court. The width of the court from the low fence ledge to the regular ledge is around 63 feet. The length of the lower court from steps to the back fence is around 90 feet.

The regular ledge is about 15 1/4 to 15 1/2 inches tall.

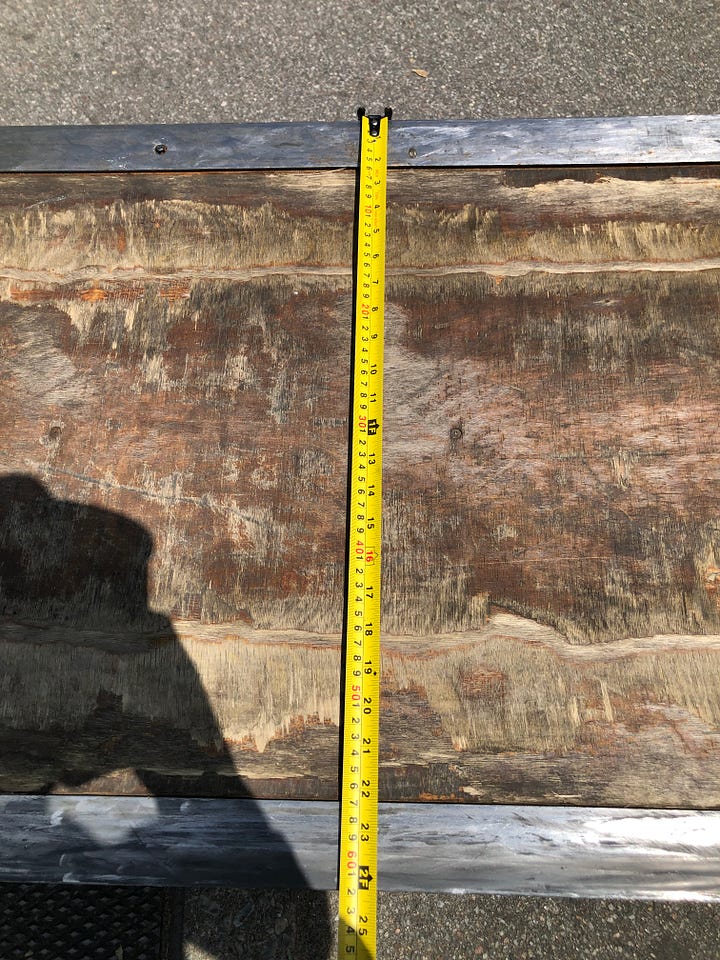

There is a small gap in the middle of the regular ledge which makes two sections. Each section is a few inches over 12 ft so in total the ledge is about 25 feet wide.

And the depth of the ledge is 23 inches.

Approaching the ledge from either the back fence or the step side, most people get on from the mid point at the earliest due to the void in between the two sections. Because of this I’ve calculated the approach from either side according to the mid point of the 25 foot ledge. From the back fence side of the court to the middle of the ledge is roughly 42 feet and from the stair side to the middle of the ledge is around 46 feet. One usually starts from a slight angle on either side of the ledge which does allow a bit more push and set up time. Even still I always feel like the 42 feet of approach from the back fence side is still not quite enough run up space. From the 46 foot stair side, which feels like there’s also a slight downhill grade from that way, I’m more or less satisfied with the run up but I’d still prefer more. Once again, I think most other people who skate reggaetone would agree.

What are our key takeaways from Reggaeton? If we estimate up a little bit the max run up space of 50 feet to approach any ledge at Reggaeton works but is not optimal. So we now know that at least 50 feet and under of approach space for a ledge is not ideal. The height of the low fence ledge coupled with the chainlink fence backing does lend itself to learning and doing tech ledge tricks. But the 8 inch depth is a bit too shallow for optimal use. The regular ledge’s height of 15 1/4 inches is a bit too high for my taste. But just barely. The ledge does have end points though so that helps lower the difficulty of most tricks. The length of around 12.5 feet seems adequate for a long slide or grind. Long enough for flip in, flip out tricks if one is capable of such technical feats. And finally the fact that there is ample space to the side of either ledge gives skaters plenty of room to carve into ledge tricks that lend themselves to that type of approach.

For our next study let’s look at the ledge spot at Thomas Boyland Park also in Brooklyn NY. Due to its close proximity to the Chauncy stop off of the J train this spot is commonly referred to as, Chauncey. Like Reggaeton, Chauncy ledges are the perimeter of a basketball court. But unlike Reggaeton whose ledges are in the middle of the perimeter of the court, Chauncy’s ledges are on the perimeter edges. Plus the back fence doesn’t run all the way across the court on one side. There is an opening on the right and left sides that allow for extra run up space. And since the ledges are on the edges of the court’s perimeter you also have more approach space from the bench/fence side.

Let’s go through the numbers at Chauncy. The height of the ledges are 15 inches.

The depth is 30 inches

and the total length varies for each of the four runs of ledges. For this study I’m only doing the two ledge runs closest to the street side of the court. For the most part they mirror the ledges on the other side. The ledge closest to the bench/fence side of chauncy has two sections. Section one is a little over 24 feet

and the section closer to the benches is a little over 5 feet. The ledge closer to the fence is two sections as well, it’s almost double the length of the section closer to the bench/fence. The section closer to the fence is 23 feet

and the the further section is almost 25 feet.

Between the two runs of ledges there is an entrance to the basketball court which is 11’ 7” wide. The total court length is about 90 feet and the width of the court is about 61 feet.

There are no end points to the ledges at Chauncey. This is the most common reason I hear people express a dislike for the ledges at this spot. The other complaint I hear is that the ledges are a bit too high. I agree with this assessment. I think the height of Chauncey is just barely over the threshold of height for a casually enjoyable ledge. But just like at Reggaeton there are other dimensional aspects of Chauncey that make it a relatively great ledge spot in spite of the fact that it’s generally considered a bit too high and has no end points.

One of those aspects is the relatively generous amount of run up space. Especially when one approaches the ledge from one of the fence openings. On those sides there is more than enough approach. On the street side and from the fence opening I usually start about 50 feet back from the fence opening when I’m going to skate the 25 foot ledge section further from the fence. (there is at-least another possible 50 feet of run up space available)

Some people start a bit closer than that. Maybe ten or so feet closer. So with more than enough available run up skateboarders tend to start somewhere between 60 to 75 feet away from the ledge being skated.

Also like the Reggaeton fence ledge, the Chauncy ledges have a backing. 30 inches in from the ledges are identical ledges stacked on top. While this backing doesn’t offer as much over shooting protection as the shallow 8 inch depth of the fence ledge it still manages to offer some safety. Unlike the 8 inch depth of the Reggaeton fence ledge the 30 inch depth of chauncy allows for the full range of ledge tricks. Lipslides, blunts, noseblunts, boardslides. The depth even allows for enough space to ollie onto the top of the lower ledge and then pop up to a slide or grind on the top ledge.

So from looking at Chauncy’s dimensions we manage to come up with the optimum amount of run up space needed for a ledge that is long enough to accommodate a substantial slide or grind. That number at the low end is 60 feet and 75 feet at the high end. We also see that 15 inches is still a bit too high.

So far we’ve been looking at spots not intended for skating. Now let’s look at one that is. At Blue park I’d like to focus on three obstacles in particular since I find them to be the most relevant to this study of ledges. Two boxes and one bench. I’ll call box #1 the good box. Box #2 I’ll refer to as the black box and then we have the bench. The dimensions of the good box are as follows. The height is between 13 3/4 inches and 14 3/16 inches.

I attribute the height difference to the angle iron sitting higher on one side. But I could be wrong about that. The width of the box is just under 10 feet and the depth is 24 1/4 inches.

The black box is 16 inches high by 8 feet wide and 3 feet in depth.

The bench is 16 inches high. 4 feet wide. and a little under 28 inches deep.

Out of the three obstacles the good box gets skated the most by the wide range of skaters who frequent blue park. The black box comes in second and the bench is a distant third. The two boxes are made of wood and have angle iron sides. The bench is made of concrete but also has metal sides. Though the metal doesn’t go over the top side. If one considers materials only, you would think that the concrete bench would attract the most usage. If one considered condition you would think that the nice solid, new looking black box would get skated the most. But instead, and it’s definitely because of the dimensions, the most tattered, rusted angle ironed box at blue park receives the most attention. The roughly 14 inch height is high enough to pop a trick onto and still feel like you’re skating a ledge instead of a curb but also low enough that a strenuous amount of effort isn’t required to pop tricks onto the box. For beginners and novice skaters it’s the perfect next height up from learning tricks on the typical 5 to 7 inch height of curbs. The 10 foot width is enough room for advanced skaters to be able to flip in, flip out and for average ledge skaters enough room is available to ollie in and flip out of slides or grinds when approached from end to end. And the 2 foot depth accommodates all the variations of slides and grinds.

At 16 inches high both the black box and the bench seem to be too high for most advanced and average skaters to casually enjoy and too high for novice and beginner skaters to learn on. Especially when a more well proportioned option is readily available in the same space. If the 8 foot box was lower I think the width might not be of such consequence but at 16 inches high and 3 feet deep the the black box seems short. And the same effect is greatly exaggerated by the bench’s short and high proportions.

If any of these were the only straight end to end ledges at blue park they would get heavily used. But because all three options are available in the same space it brings to light evidence of general preferred ledge dimensions amongst a wide range of skateboarders.

After analyzing the heights of the ledges at Flushing, Blue park, Chauncy and Reggaeton I think it’s safe to say that the range for a proper ledge height in a skate park setting should be between 13 1/2 and 14 1/4 inches. Preferably no lower than 13 inches and maybe a 1/4 inch above 14 1/4 inches would still suffice. The width of the ledge should be no less than 10 feet and the depth should be at least 20 inches unless the ledge has backing, then the depth should be around 30 inches. Once a ledge of this height, width and depth is in a skate park ledges of other heights, widths and depths could be added. But in every skatepark that plans to incorporate ledges into the design a ledge of the above proportions should be the first priority. That ledge should also have at least 60 feet of run up space but preferably 75 feet from both sides. There should be at the minimum 10 feet of space to the side of the ledge and that same amount of space should extend out for the 60 to 75 feet of run up on either side. All of this together means that the general footprint needed for a properly designed ledge is between 160 to 170 feet wide by 10 feet deep.

If you’re wondering why I don’t suggest using a quarterpipe as a drop in, I’ll explain briefly here. Using a quarterpipe as a device to get speed to a ledge creates instant conflict between those who want to skate the ledge and those who want to skate the quarterpipe. And also those who want to skate the ledge and the quarterpipe. It’s common in skating for skateboarders to specialize. Even in the age of skateparks that were designed to make every skater conform to an all terrain style of skating, specialized skating still thrives. When a person who specializes in ledge skating is skating a ledge they often don’t want to drop in on a quarterpipe to get speed. They tend to want to start from flat and either throw down or take a couple pushes. This means that just skating in their preferred manner will inevitably put them in the way of someone who wants to skate the quaterpipe. If a skater specializes in transition skating then they probably have little to no use for the ledge set up in the roll away/ run up zone of the quaterpipe. In fact it’s quite often a hindrance to them. And even if a skater does conform to the all terrain style of skating that the skate park design dictates to them, the specialized ledge skater is still going to be in their way. This is a reality of how skateboarding works. If a designer uses a quaterpipe as a device for getting speed to a ledge then they are either blindly ignorant of this fact, or consciously ignoring this fact and then for some reason choosing to design an obstacle usage conflict into their skate park. I’ll leave it at that for now.

We’ve figured out our ideal height for a ledge. A span of preferred width. A range of proper depth and an optimal footprint of space around the ledge. So lets talk layout.

Since the footprint of the optimal amount of space for a ledge is so long and wide and because a person who specializes in ledge skating usually also specializes in flat ground skating I think something like a Chauncy or Reggaetone basketball court layout works well as a space for ledge skating. This would mean that the ledges would be on the perimeter and the flatground would be wide open. The width of 65 feet ( which is roughly the width of Chauncy and Reggaeton) from ledge to ledge provides plenty of space to the side of each ledge and still leaves plenty of space for people to skate flat ground in the middle of the space without running into people skating the ledge.

On one side of the skate court could be our ledge of optimal height and on the other side could be a curb of similar width and depth. This would provide a nice stepping stone on which beginner and novice skaters could progress and it would provide a nice environment for more advanced skaters to experiment with new tricks and perfect the ones they already know.

Benches for sitting could be provided on either end of the run up so skaters and even non skaters can watch people skate without being in the way.

Four skaters could be skating at the same time and not be in each others way. Two could be skating flatground, one skating the curb and the other skating the ledge. Because the sight lines wouldn’t be blocked by any obstacles in the middle of the court and because no quarterpipes would be flinging skaters around at high speeds the person skating the ledge could potentially carve around after their ledge trick and hit the curb or flat ground without getting in anyone’s way. And vice versa for the person who skated the curb.

People waiting for their turn to skate the ledge, curb or flat ground would have ample space to stand and chat with each other and the people sitting on the benches.

This would create a skate environment and a park environment. Unlike most skateparks which realistically shouldn’t be called skateparks. They should be called what they actually are, a competition course. More appropriately a practice competition course.

A quarterpipe could be placed in its own section and it could be given the space, respect and attention to detail it unfortunately doesn’t receive in modern skateparks. I won’t get into the details of quarterpipe dimensions in this article, it’s already very long. But basically a very wide quarterpipe made of a material more interesting than concrete or wood. Ample flat ground at the bottom for approach and benches for sitting by the start of the approach to the quarterpipe. As mentioned earlier this type of set up creates a skate and park environment.

In a separate but similarly sized area there could be a beginner section with some recessed curbs for ride on grinds to help beginner skaters easily get the feeling for grinds and slides. Small quarterpipes perhaps with a backing like Reggaeton (not a chainlink fence though and deep enough to allow for atleast a rock and roll) to help beginners safely and more easily learn lip tricks. Of course more advanced skaters would enjoy the beginner section as well. Benches for sitting would also be strategically placed in this section.

This is just one idea for a different style of skatepark layout. And these are just a few obstacle ideas that would be placed in these layouts to help give a more detailed description of how a skate park could be laid out differently and better. But don’t worry I got plenty more on the way in subsequent articles.

Now let’s get back to ledges because we still haven’t discussed shape or materials.

There are only two ledge shapes that can properly accommodate a broad range of skaters with different abilities and preferences. A rectangle and a square. A ledge should never have any curve, low to high slant or high to low slant whatsoever unless a straight ledge of optimal dimensions already exists in the same space. Even a slight curve or tilt disrupts the learning process and enjoyment of ledge tricks greatly.

When a skater is attempting a ledge trick their speed tends to slightly vary on each try. Where they pop from and how high or low they pop usually varies on each try as well. That means that, potentially, on each different try the skater will be landing at a different point in the curve or slant of the ledge. On a straight ledge if a skater lands a few inches further on the ledge or a few inches back it doesn’t matter. The weight distribution needed to grind or slide will be the same. On a curved or slanted ledge landing a few inches further into the curve/slant or a few inches back will potentially, drastically change the weight distribution needed for a proper slide or grind. If a skate park designer skates ledges they should be aware of this fact of skateboarding. No one is making a skate park designer curve or tilt a ledge. There’s a possibility that they are simply ignorant of this fact. If that’s the case then they aren’t qualified to design a skatepark. They obviously lack a well rounded knowledge of how skateboarding works. If they are consciously ignoring this fact and then pointlessly making the learning process and act of casual skating harder and less enjoyable then the designers motives must be called into question. Once a ledge of proper dimensions exists in a space then (if enough space is available) a curved or tilted ledge could be added. But the dimensions of both would need to be put through the same rigorous usability analysis that we just went through to come up with our ledge and footprint dimensions.

As far as materials go angle iron should not be the go to choice for ledges. Polished concrete that’s kept waxed and or painted can last for decades. Granite that’s kept waxed can last for decades as well. Maybe longer. An array of materials should be experimented with as ledges. Angle iron is good for tech grind tricks so it should still have its place but polished and or painted concrete and granite should be the most prevalent materials used for ledges in skateparks. Limiting grindable and slideable material in a skate park to metal only is flat out ridiculous. Grinding and sliding different materials and textures is one of the most lively sensory experiences encompassed in the act of skateboarding. This is common knowledge amongst street skaters. Unfortunately this knowledge hasn’t managed to make its way into the minds or budgets of most skatepark designers. All of that just to gain an understanding of how to properly place and design one obstacle in a skatepark.

I think it’s safe to say there are a great number of minute details that are overlooked in modern skatepark design. Perhaps paying attention to the minutiae of obstacle dimensions, and optimal placement of those obstacles to allow for full usage is one of the ways in which we can vastly improve our skateparks.

Very knowledgeable.

Hi Dave,

This in depth writing you're doing is really difficult and is a immense service to skaters in this country at least. Skatepark design is in somewhat of an arrested development here. In this era of landscape design being entirely uninterested in the plaza styles where skateboarding incidentally thrived (re: Love and Muni getting greened up), its really important that we as skaters take stock in very fine detail of what actually makes a great space for skateboarding. Its about park scaled compositions that function well and are made up of very minute and interrelated details. Cogently switching between those scales is difficult in conversation and in writing. I think you're doing a great job of breaking it all up. Its an immense challenge.

You're absolutely right that the cultural component has evolved since Skater's Island and skatepark design in many ways has not. Having grown up skating almost exclusively street and then working for Breaking Ground Skateparks, a design/build/ skate ethos grown out of Burnside, I have learned a lot in straddling those two sects within skating (there's pages I could write about the coping debates but I will hold off for future posts).

That 'older ethic' that lead to conflict over bike pegs is central to the arrested development of current skatepark design but that conflict is still grounded in a material disfunction. For the most part I think the effects of urethane and aluminum and plywood on the cityscape is unsightly but ultimately can be defined as "use" rather than damage. Whereas steel pegs cause a lot more of cracking, chipping and breaking, which skaters are often blamed for as BMX bikes are never a municipally banned activity. I have experienced it in the disappointment of losing ledge spots to damage but also the frustration in fielding complaints from city officials whom I've been lobbying for better skateparks. I think that this distinction remains important for design/ build conversations despite progress in cultural overlap.

But yeah all that to say:

Yes! I too would love to experience more granite and concrete ledge grinds in skateparks. This page rules. Looking forward to what you write next