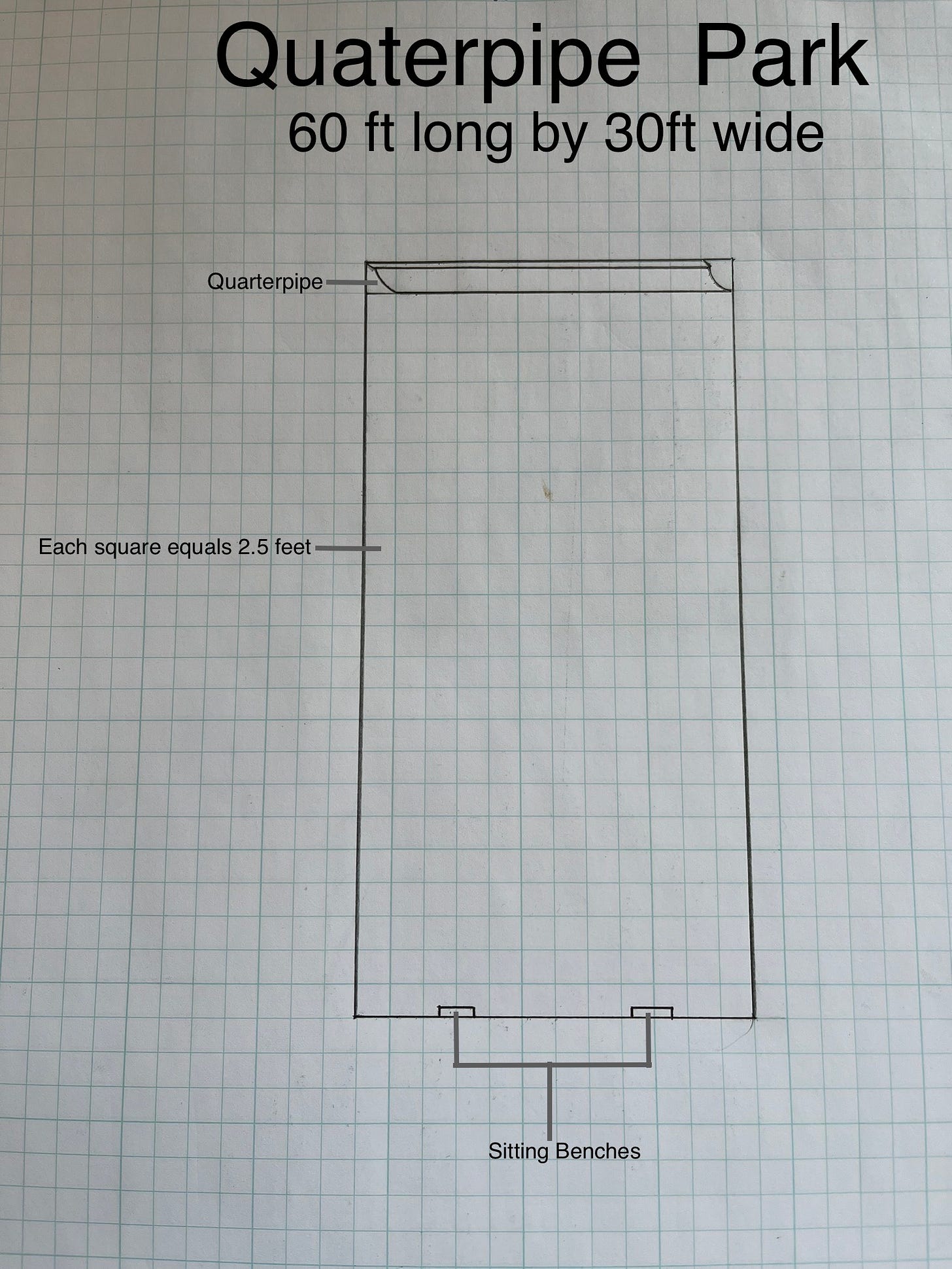

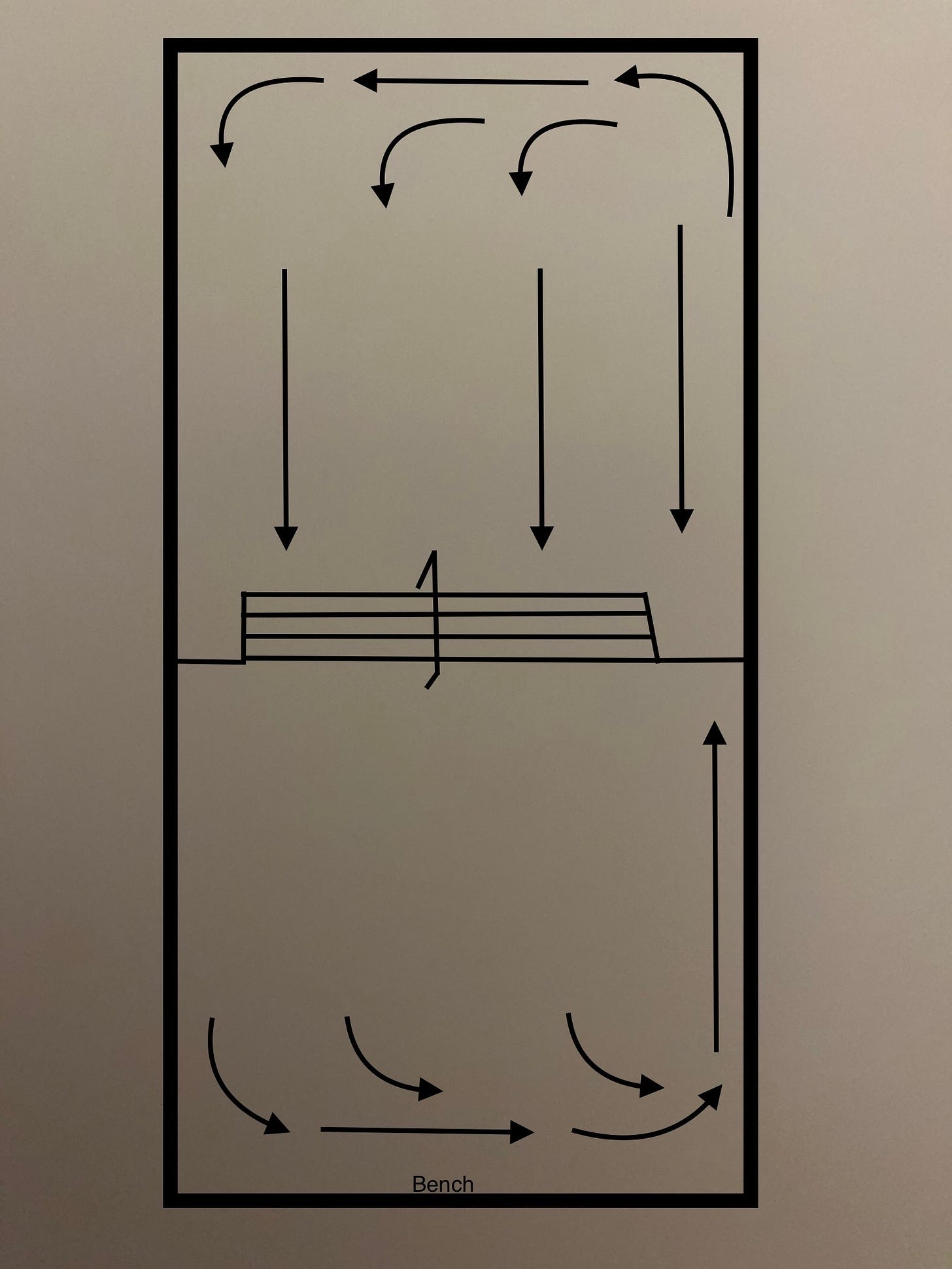

The Quarterpipe Park

*Rendered in a weird mix of top and straight on view.

Think about quarterpipe spots that exist outside of skate parks. Street transitions. There’s usually just one quarterpipe. That quarterpipe is often all one size. Not really much else to skate at the spot. Yet street transitions are highly coveted amongst skaters. While we do mimic the quarterpipes themselves in skateparks the spatial qualities of the areas where these street transitions originally existed are completely ignored. What I’m suggesting is that we give an equal amount of attention to the spatial aspects of street quaterpipe spots.

The quaterpipe park does just this. But one feature potentially makes this park even more enjoyable than street transition spots. The small size of the space means that while people aren’t skating they have an edge on which to linger. Not just standing room along the edge but also benches for sitting. Often but not always the quarterpipe in a street transition spot is on the perimeter of a space which puts the preferred starting/ lingering point in a wide open area.

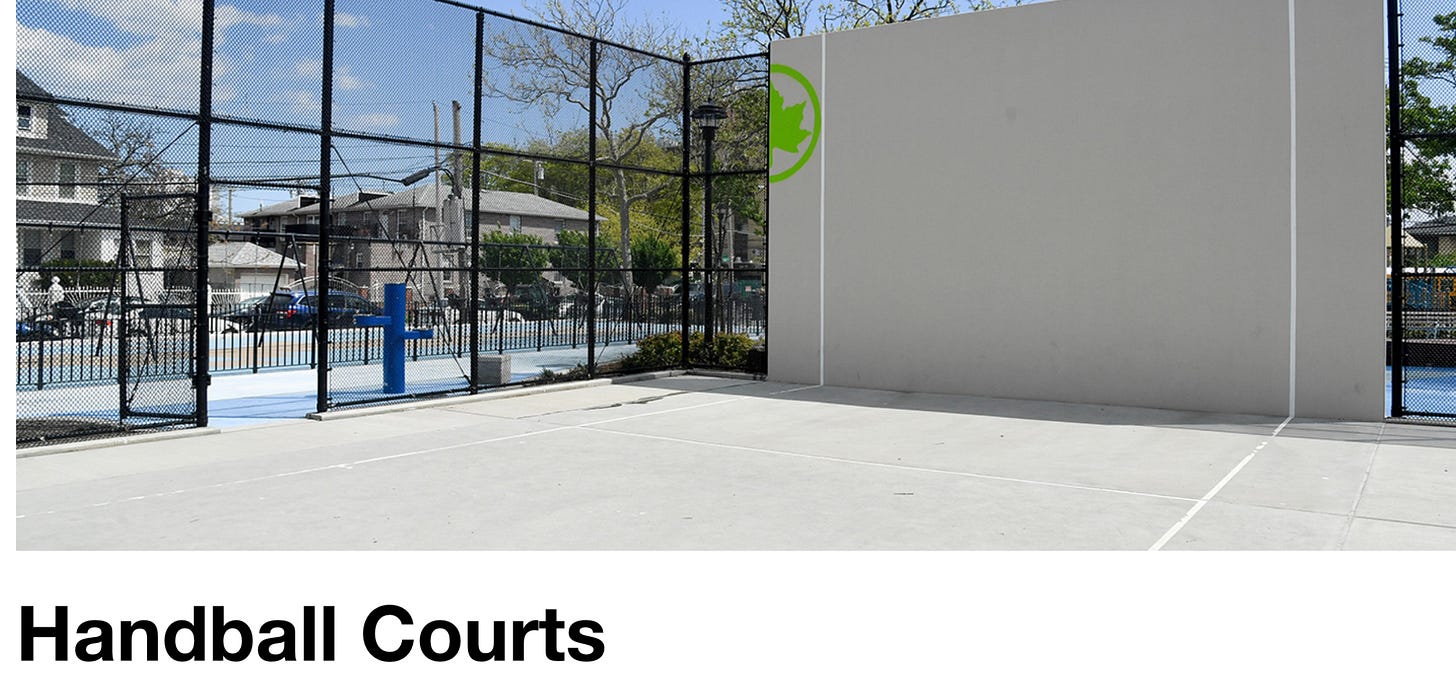

I have this example at 60 feet long by 30 feet wide. The length of this park would accommodate a taller qp. Probably one 6 feet or even higher for this length. If the quarterpipe is lower in height you could cut the length down significantly. An NYC handball court size would work perfectly for a smaller quarterpipe.

The typical handball court size is 40 feet long by 20 feet wide. There’s also a wall in handball courts that is between 12 to 14 feet high. It’s a perfect set up for a small single quartepipe spot. Including the wall. Including a high wall behind a quaterpipe provides a kind of subconscious comfort for people skating the quarterpipe. And not only would it help to define the space it would also be skateable.

The skate traffic in the quarterpipe park is pretty apparent. I’ll forgo the graphic for this one.

As far as the movement of skating and socializing goes I think the quaterpipe spot takes the cake. There’s just one side in the space where people will congregate and wait to skate. Everyone will likely see all of the trick attempts that occur. It’s an intimate space. It’s the kind of space where only mundane tricks could go down during the course of a skate session and everyone could still have a great time. It’s the same effect I discussed in Urban Plazas. When everyone is watching each other skate you see the battle each person goes through to make their trick. If someone who’s not that experienced at skating is trying a simple front 5 O grind and it takes them thirty tries to make it but everyone’s been watching the battle, all who are watching are probably gonna be psyched for our novice friends simple trick. If a more experienced skater does something remarkable the crowd is likely to go wild. This type of watching, reacting and chatting in between tricks builds the energy in a session. Everyone benefits from this rotation. It’s social. It’s motivational. It’s one of the integral factors that creates the distinct culture of street skating. All of these positive outcomes emerge from combining the waiting in between trick area with the viewing/seating area and placing it in a zone that doesn’t block any skate obstacles.

There’s another positive aspect of this strategically placed zone. Pedestrians can be in the space without being in the way of people skating. This makes it possible for skaters to experience the type of random social interactions that occur with non skaters while street skating. Think of all the beloved clips (“Name is Psycho” , “Nice to meet you I’m an artist”) in skate videos of non skaters who are hanging out in the same space people are skating and the camera turns their way for a memorable comment or rant. Or think of your own instances of being out street skating and all the funny, strange, cool, and perhaps even sketchy encounters you’ve had with non skaters that make the experience of skating that much more rich. It’s really unfortunate that the layout of modern skateparks makes these types of interactions very unlikely to occur.

The zones in modern skateparks that could be used for the waiting in between trick/viewing/sitting area are most commonly occupied by quarterpipes or embankments. The quarterpipes or embankments are typically on at least two sides of the park. Usually across from each other. They might even be on all four sides. Besides the potential anti social effects caused by this layout another adverse effect arises which has to do with a subject we touched on in part two of this article. That subject is, as humans, how our sense of sight works. We learned that “Human movement is by nature limited to predominantly horizontal motion at a speed of approximately 5 kilometers per hour (3 mph), and the sensory apparatus is finely adapted to this condition.” We also learned that our horizontal field of vision is expansive while our downward field of vision is much more limited and our upward field of vision is even more limited than our downward field of vision. Quarterpipes and embankments clustered together create a range of elevations and they allow skaters to pick up speed quickly and then all the pump humps and embankments clustered in the middle help to maintain that high speed. Both of these factors make it very difficult for skaters to accurately judge where more than a few skaters currently in motion or potentially in motion are or will soon be in the skate park at any given moment. We don’t run into and get in each others way because we’re all assholes snaking each other. That does happen of course. But most of the time it’s just due to simple human sensory limitations. Skateparks are not designed with the limitations of our human senses in mind. They are not designed to human scale. They are designed for one skater in motion doing trick after trick on obstacle after obstacle. Here’s a simple way to think of it.

Modern skateparks are designed for;

1. One skateboarder in motion.

The parks I’m suggesting are designed in this order;

1. Human scale

2. Skateboarders in motion

3. Skateboarders and non skateboarders not in motion

This simple perspective change yields vastly different layouts. Both enjoyable in different ways. Both fulfill a need amongst skaters. One style of skatepark design cannot fully accommodate all of the many different ways skateboarding can be practiced and enjoyed.

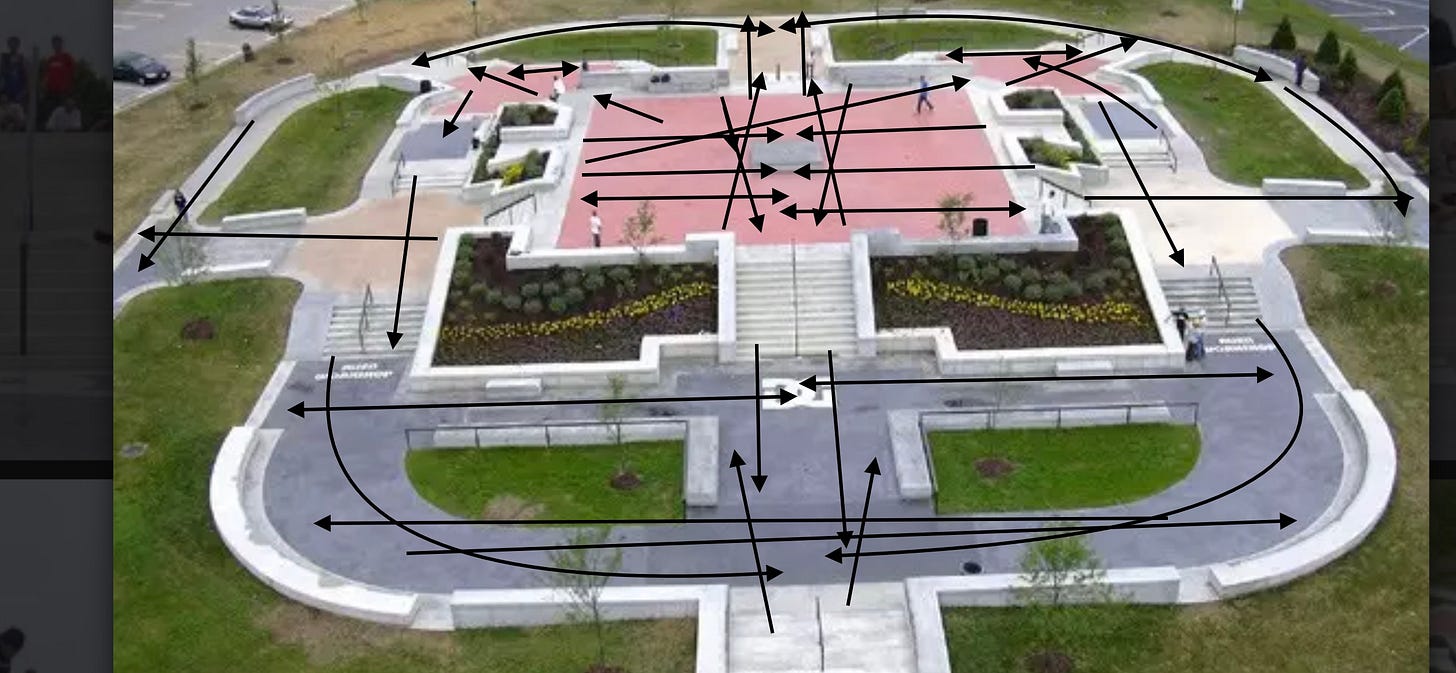

On a side note, since I’m discussing different styles of skatepark design I’d like to clarify something. I think many people consider transition parks and plaza parks to be two different styles of design. I disagree with this assessment. I would argue that the only difference between these two parks are the obstacles. The obstacles in street plazas are placed based on the perspective of one skater flowing through a park hitting obstacle after obstacle just like the flow parks. Because of this the same clustering that leads to obstacle usage conflicts, which then leads to competition for space and then to potential anti social sentiments and behavior occurs in both types of parks. Different obstacles but the same design style. Take the Kettering skate plaza in Dayton Ohio for example.

The arrows in the picture above represent all the directions skaters move in the plaza to skate the obstacles.

The cross traffic in this park is maybe worse than any quarterpiped out cluster park that exists. The run up/roll away of two of the ledges near the foreground actually puts skaters right at the bottom of the largest stair set in the plaza. Just to call out one of the more egregious cross traffic scenarios in this plaza. This park doesn’t contain a single quarterpipe. Yet it still has the same issues as modern flow parks. The only sitting/ viewing area that’s out of the way of people skating in the entire plaza are the ledges that line the platform space up top. But with all the cross traffic up there those zones can still get hectic. A skate plaza is not the equivalent of the spaces I’m suggesting. The aspects of skating that flow parks can’t accommodate are the same ones modern plaza parks can’t accommodate either.

All that being said I still enjoy skating the Kettering plaza. If I’m visiting friends in Dayton we’ll make a point to skate there. Of course we go on a weekday and on the early side and for the most part all we’ll skate is the platform up top. Which when the plaza isn’t crowded can function like a street spot.

Also I don’t expect anyone to hate the Kettering plaza after reading this and looking at my lovely diagram. Once again I’m just taking a closer look at how spaces made for skating function and then drawing conclusions.

Back to quarterpipes. Designing a skatepark from the perspective of one skater flowing through a park at a time can make the process of learning how to skate a quaterpipe more difficult than it should be. For instance, let’s say a skater wants to repeatedly try a trick on a quartepipe at a skatepark in order to learn a new trick. They’ll likely have to stand near a ledge, flat bar, pump hump or any number of other obstacles in between tries. This then puts them in the way of other skaters who want to skate those other obstacles. In order to avoid being in the way of those other skaters our friend skating the quarterpipe would have to go to the other quarterpipe across the park, drop in, ride over a pump hump or pyramid, or ollie up a ledge or curb and drop off, then finally set up for their qp trick. Additionally they would have to dodge and or time their approach to avoid all the other skaters hitting all the other obstacles along their path between the two qp’s. Skate parks are typically filled with quarterpipes. Yet rarely are any of them placed in a way that makes them an easy obstacle on which to learn tricks and casually session with friends.

Now let’s look more into how socializing on the many quarterpipes in skateparks plays out. Socialization on the deck of a quaterpipe is not optimal. Even if the deck of the qp is relatively large. Someone still might want to ride out of the quartepipe and arch a manny and then ride back into the transition. Someone might chuck a backside boneless in your face. A board might fly out and ding you in the head while you’re chatting with your friend. I’m not saying that it’s impossible to socialize on the deck of a qp but I am saying that for all the reasons mentioned above and more the top of a quarterpipe just isn’t an optimal place to socialize in between tricks. But quarterpipes are placed on the edges of skateparks, which as we’ve already learned is where, as humans, we tend to want to linger and socialize. So while placing quarterpipes and embankments on two or more edges of a skatepark does create a great flow park design it quickly degrades the quality of socialization that can occur in the space. Especially as the number of people skating the park rises.

As far as modifications to the qp park would go, obviously heights would vary. The higher a quartepipe the longer the space would need to be. And vice versa for a lower quartepipe. But the quaterpipe spot could also be the bank to ledge spot. Or just the bank spot. The bank or bank to ledge could be transitioned at the bottom like the Brooklyn banks or it could be just a slant like South bank in London. The bank to ledge could be a bank to curb instead as well. As far as adding channel gaps or extensions in these parks I would not add them unless there is already at least 30 to 40 feet of straight lip. The max width of a qp park should be no more than 80 feet. This limitation is based on how humans sense of sight functions.

Brick, granite, concrete, even painted asphalt could all be possible materials used for these spots. They could be used in combination as well. Concrete ground and a brick quartepipe with granite caps for coping. Painted asphalt ground and bank with a polished and waxed concrete ledge. Just to name a few. Just like in the Ledge Court the subtle variations in the size and materials of these parks create the variances as opposed to regular skateparks where the different combinations of obstacles clustered into a space create the variances.

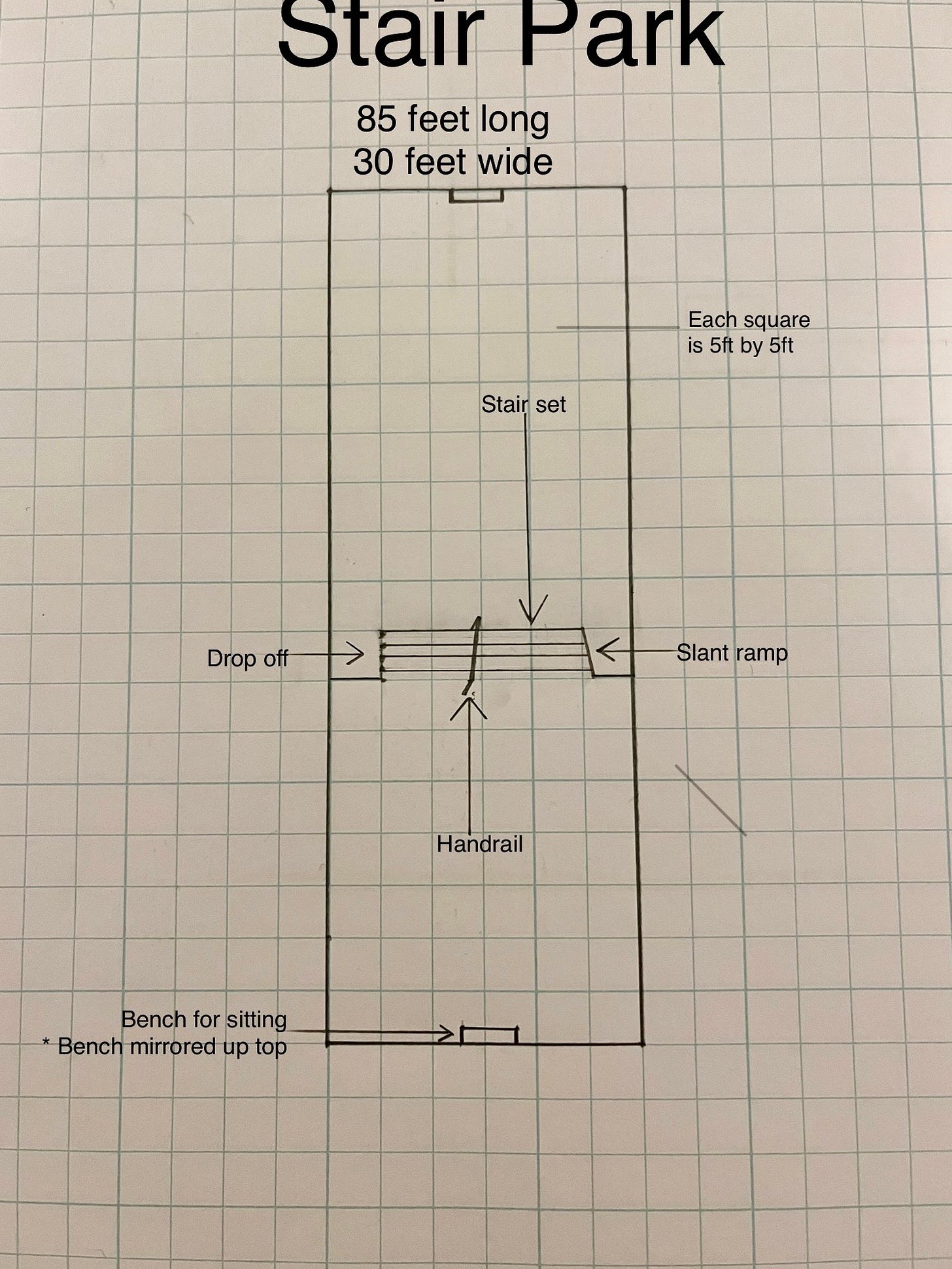

The Stair Park

* Rendered in Top View

I have the example of the Stair Park at 85 feet long and 30 feet wide to show that when only one or two styles of skating are being catered to the space can potentially be very small. I think 100 feet long would be better (especially if there’s more stairs) but 85 feet works. As far as width goes I would say 50 feet is about as wide as the stair park should span. Any wider and the increased width would likely lead to cross traffic.

In this example I have a four stair. Since that’s a relatively small set of steps I have a drop off on one side to accommodate beginner skaters. This allows them to get used to the drop of the stairs without having to deal with the length of the stairs. This provides an incremental step that aids the learning process. The inner edge of the drop off could also be waxed up and then used as a ride on grind to drop. At around 7 or 8 stairs I would forgo the drop off and the slant because they are obstacles meant more for beginner skaters and instead just have hubbas or out ledges on either side. If a person can skate an 8 stair I would say they’re no longer a beginner.

The skate traffic in the Stair Park moves mainly in two directions. The semi circle carve on this one would occur after a skater launches out of the slant ramp then carves around to hit the stairs or the drop or vice versa. Since the stairs are relatively small and so is the drop, skaters could ollie up both but in stair parks with more steps going upstream would be an option for very few skaters.

The socialization in the stair park functions along the same lines as the ledge court. The short ends of the perimeter where the standing and sitting areas are placed are once again the zones where socialization can occur in a mostly unencumbered way. There’s plenty of room for skaters to wait in between tricks without blocking obstacles and this set up promotes the rotational effect of skater/spectator.

In modern skateparks stair sets will have cross traffic on either the landing or the run up or both. Or even more frequently there’s another obstacle such as a quaterpipe or embankment petty close to the landing of the stairs. So while most skateparks do have stair sets hardly any have steps that don’t require a healthy amount of patience and timing to wait for the cross traffic or oncoming traffic to clear. Unless of course one is skating the park alone or with only a few others who are all skating in a similar fashion.

Pictured above is the set of stairs at LES Coleman skatepark. It’s a great stair set. The hubbas and rail are proper heights, lengths and they have a not too steep, not too gradual pitch as well. However one of the problems is that if even only a few people are dropping in on the qp (shown in the photo) to skate the pyramid (not pictured) one will have a hard time rolling away from their handrail/ hubba / stair trick without running into someone dropping in on the quarterpipe or a skater coming from the pyramid to the quarterpipe. That’s just the roll away from these stairs.

The approach to this stair set also becomes increasingly difficult to navigate as the number of people skating the LES park rises.

In this photo we see that the approach is at the top of a quarterpipe with a relatively spacious deck. Plenty of space to approach the stairs when no one else is skating the park. But the way it plays out in LES is that once a few people are using the qp as they’re starting point for skating the park they tend to linger in the middle of the run up to the stairs. They really have no other choice. They could lean up against the fence. But that’s a long way to travel to get to the qp in time to get your turn at a somewhat crowded skatepark. They could stand closer to the edge of the qaurterpipe but standing too close to the edge of a qp is a very basic no no of skatepark etiquette for obvious reasons. So the person skating the stairs hinders the person dropping in on the qp’s skating and the person skating the qp hinders the stair skaters session as well. Once again we see that the clustering of obstacles leads to competition for space which then leads to obstacle usage conflicts which can then lead to anti social sentiments and behavior.

The quick and easy way to picture the conundrum of this set up is to apply the shadow concept I mentioned while discussing The Ledge Court.

The usage shadow cast by the stair/hubba/rail set up overlaps the usage shadow cast by the qp at the bottom of the stair set and the deck of the qp which is the run up to the stair set. Wherever shadows cast by obstacles overlap each other an obstacle usage conflict will occur.

As far as modifications go for the stair park the options are numerous. Long, low sets of steps with medium height rails and hubbas that are only slightly tilted. Round handrails. Square rails. Out ledges instead of hubbas. Double kink rails. Just to rattle off a few. The Kettering skate plaza actually has great examples of all the different styles of stair sets. You could just take each one of those stair set ups and place them in their own zone with appropriate run up and roll away space and voila you’d have a plethora of perfect stair spots.

Of course materials and textures could vary greatly as well. Stone Paver run up with brick landing. Granite hubbas. Concrete handrails. Just like the Ledge court each stair park could be unique and still retain the social and spatial qualities of the core layout.

(Conclusion in part four)