Life Between Skate Tricks ( part two)

The Hidden Dimension

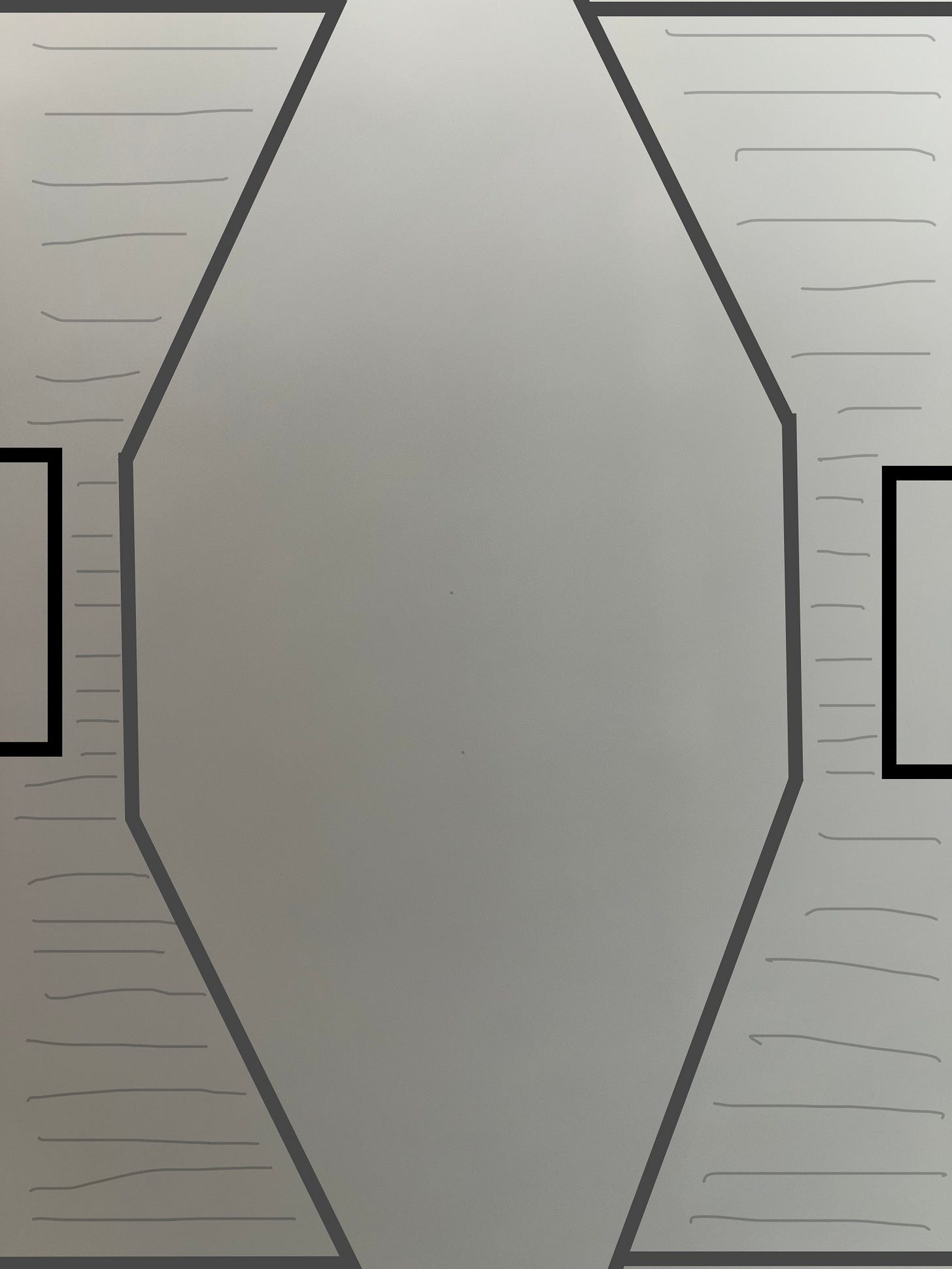

First up is the Ledge Court.

*Rendered in top view

The Ledge Court is meant to accommodate ledge and flatground skating only. At 70 feet wide the park is about the same width as a basketball court. At 130 feet long it’s almost the length of 1.5 basketball courts. As far as public spaces go that are allotted to sports and other activities it’s not that big of a space. Compared to other skateparks it is also not that big of a space. However a skatepark of this size would likely have quadruple the amount of obstacles if not more. But every detail of the ledge court is purposeful.

In order to thoroughly enjoy flatground skating I’ve left the middle completely open. Technically you only need a small amount of space for flatground skating to be possible. But one of the goals of this design is to fully accommodate flatground skating. Casual, enjoyable flatground needs wide open space. Enough area to carve into a trick before you pop if that’s how one does some tricks. Room to roll away sketchily and not run into anything. Enough space for two people to skate flat at the same time and not crash into each other or hinder each others skating. That’s why I’ve left such a relatively open expanse in the middle of this court.

The two ledges in the space are both placed in the middle and on the perimeter of the two long sides because obstacle placement dictates the movement of skaters and also where they will stand when they are not on board and in motion. A helpful way to visualize this concept is to imagine that every obstacle placed in a space casts a shadow. The shadow represents the space needed to have enough run up/roll away room and space next to the obstacle to attempt and do tricks. It also accounts for the standing room in which to linger in between trick attempts.

The picture above shows the outlines of the shadows cast by the two ledges in the ledge court. Within each shadow lies the space needed to stand while waiting in between trick attempts. The space needed to approach and roll away from tricks done on the ledges. And the space needed to the side of the ledge to perform tricks. Notice how there are no other obstacles in the shadow zones and the shadows of the two obstacles in the space do not overlap or intersect at any point.

The sitting benches are placed on the perimeter of the two short ends and they do cross over into a portion of the shadow zone in this design but the benches don’t run across the entire way. This allows skaters to sit in between skating and quickly switch back and forth from skating to socializing while still maintaining a clear view of friends and other skaters.

Another reason why I’ve placed the standing and sitting room for the court on the perimeter is due to a phenomenon called the “edge effect”.

This excerpt is from a book by Jan Gehl called Life in Between Buildings: Using Public Space:

Popular Zones for staying are found along the facades in a space or in the transitional zone between one space and the next, where it is possible to view both spaces at the same time. In a study of the preferred areas for stays in Dutch recreational areas, the sociologist Derk De Jonge mentions a characteristic edge effect. The edges of the forest, beaches, groups of trees, or clearings were the preferred zones for staying, while the open plains or beaches were not used until the edge zones were fully occupied. Comparable observations can be made in city spaces where the preferred stopping zones also are found along the borders of spaces or at the edges of spaces within the space.

The obvious explanation for the popularity of edge zones is that placement at the edge of a space provides the best opportunities for surveying it. A supplementary explanation is discussed by Edward T. Hall in the book The Hidden Dimension, which describes how placement at the edge of a forest or close to a facade helps the individual or group to keep its distance from others.

At the edge of the forest or near the facade one is less exposed than if one is out in the middle of a space. One is not in the way of anyone or anything. One can see but not be seen too much, and the personal territory is reduced to a semicircle in front of the individual. When one’s back is protected others can approach only frontally, making it easy to keep watch and react, for example, by means of a forbidding facial expression in the event of undesired invasion of personal territory.

So by placing the benches on the short ends of the space and also leaving room for standing this layout caters to humans natural inclination to linger at the edges of a space. This, in turn, likely ensures that skaters (and non skaters as well) will be out of the way of those actively skating the ledges and or flatground. And if a person actively skating decides to stop to rest, chat or watch others skate they have sufficient standing and sitting room within the viewing area of the space to do so.

The skate traffic in the ledge court only moves in two directions. With the exception of skaters carving a semi circle at either end of the perimeter after a ledge or flat ground trick in order to hit the ledge on the other side or do a flatground trick going the other direction. This effectively puts the only cross skate traffic at the perimeter of either side of the space where people are standing or sitting. That means the people waiting to skate can easily see and adjust their own timing for approaching the ledge while the other skater makes their semi circle carve. If two skaters are carving semi circles at the same time from opposing directions they would have plenty of time and space to see each other and avoid a collision.

That covers the basics of how skating would function in the ledge court. But now let’s look at how socializing would function in this space.

The following is another excerpt from Life Between Buildings:

Familiarity with the human senses and how they function and the areas in which they function — is an important prerequisite for designing and dimensioning all forms of outdoor spaces and building layouts.

Because sight and hearing are related to the most comprehensive of the outdoor social activities — seeing and hearing contacts — how they function is, naturally, a fundamental planning factor. A knowledge of the senses is a necessary prerequisite also in relation to understanding all other forms of direct communication and the human perception of spatial conditions and dimensions.

Human movement is by nature limited to predominantly horizontal motion at a speed of approximately 5 kilometers per hour (3 mph), and the sensory apparatus is finely adapted to this condition. The senses are essentially frontally oriented, and one of the best developed and most useful senses, the sense of sight, is distinctly horizontal. The horizontal visual field is considerably wider than the vertical. If one looks straight ahead, it is possible to glimpse what is going on to both sides within a horizontal circle of almost ninety degrees to each side.

The downward field of vision is much narrower than horizontal, and the upward field of vision is narrower still. The field of upward vision is reduced further because the axis of vision when walking is directed approximately ten degrees downward, in order to see where one is walking. A person walking down a street sees practically nothing but the ground floor of buildings, the pavement, and what is going on in the street space itself.

Events to be perceived must therefore take place in front of the viewer and on approximately the same level, a fact that is reflected in the design of all types of spectator spaces — theaters, movie houses, auditoriums. In theaters balcony tickets cost less because events cannot be seen in the “correct” way; and no one will accept sitting a level lower than the stage floor. Another example that illustrates the vertical limitations of the field of vision is the merchandise display in supermarkets. Ordinary household products are placed below eye level, on the shelves nearest the floor, while shelves in a narrow band just at eye level are filled with unimportant, unnecessary goods that stores want customers to buy impulsively.

Everywhere that people move about and are engaged in activities, they do so on horizontal planes. It is difficult to move upward or downward, difficult to converse upward or downward, and difficult to look up and down.

One more from Life in Between Buildings:

One can see others and perceive that they are people at a distance from 1/2 to 1 kilometer (1,600 to 3,200 ft.), depending on factors such as background, lighting, and particularly, wether or not the people in question are moving. At approximately 100 meters (325 ft.), figures that can be seen at a greater distance become human individuals. This range can be called the social field of vision. An example of how behavior is affected by this range is the sparsely populated beach where individual groups of bathers distribute themselves at about 100 meters (325 ft.) intervals, as long as there is available space. At this distance the groups can perceive that there are others farther along the beach, but it is not possible to see who they are or what they are doing. At a distance of between 70 and 100 meters (250 to 325 ft.) it begins to be possible to determine with reasonable certainty a person’s sex, approximate age, and what that person is doing. At this distance it is often possible to recognize people one knows well on the basis of their clothing and the way they walk.

The 70 to 100 meter (250 to 325 ft.) limit also affects spectator situations in various sports arenas, such as football fields. The distance from the farthest seat to the middle of the field, for example, is usually 70 meters (250 ft.). Otherwise spectators cannot see what is going on.

Not until the distance is considerably shorter does it become possible to perceive other people as individuals. At a distance of approximately 30 meters (100 ft.), facial features, hairstyle, and age can be seen and people met only infrequently can be recognized. When the distance is reduced to 20 to 25 meters (60 to 80 ft.), most people can perceive relatively clearly the feelings and moods of others. At this point the meeting begins to truly become interesting and relevant in a social context.

The short ends of the Ledge Court are 70 ft. wide. These are the two areas where socialization will occur in this space. Since 60 to 80 feet is the distance when socialization really becomes interesting not only does the width of the park accommodate skating it also accommodates socialization. The events to be perceived in the Ledge Court are the ledge and flatground skating. The sitting benches and standing area are frontally oriented at eye level towards both. Because of humans expansive horizontal field of vision at eye level a person standing or sitting on those short ends would have a full view of what’s happening in the ledge court. There’s no pyramid, ledge stack or quarterpipe blocking the field of vision. This creates a commonality amongst all of the people in the court. Even if a person is focused on watching a ledge on one side of the court they would still see a good portion of the court in their peripheral vision. Everyone is essentially watching the same events unfold. Plus where people are standing isn’t blocking any obstacles. The ledge is far enough away from the standing/sit zone that no one should need to jockey for position along this area. Which means that while one is standing or sitting they can be completely at ease. Because everyone is frontally oriented towards the skating that’s happening if someone’s board zings out from missing a ledge or flatground trick, it would very likely be seen in time to avoid someone catching a shark bite to the shin. All of this would overall create a relaxed environment. Which would then lead to a social environment.

I’ve found that in spaces similar to the Ledge Court, such as Chauncy and Reggaeton, a natural order tends to develop amongst people skating in them. Everyone is clearly in each others field of vision and standing on the same level on either of the two sides. Without any conversation it can be quite easy to work out a rotation of skating that works for everyone. A person who consistently snakes other skaters will find that once they aren’t actively skating they have to stand pretty close to everyone else in the space. The two short edges are the only options of places to stand if they intend to keep skating and snaking. Standing right next to someone or perhaps multiple people you just offended is uncomfortable for even the rudest of folks. So by design this layout encourages good etiquette. It’s also easy for someone who just started skating or someone who isn’t familiar with the space to figure out the general movement of the court. Although as I’ve seen with my own eyes at Reggaeton it can sometimes take about 5, 10 minutes to sink in.

I was skating Reggaeton with a few friends a year or so ago when a group of about ten skaters showed up who were likely from out of town. They walked in and stood together somewhat close knit near the middle of the court. Suddenly they dispersed and started skating diagonally, horizontally, all directions. Those who weren’t skating were standing in weird places. My friends and I stopped skating and observed. My friend Joe likened the dispersal to someone kicking an anthill. Slowly we started skating again and after about 10 minutes or so the crew of skaters were all standing on either end of Reggaeton taking turns with each other and us, skating the ledges and flat just like experienced locals. We didn’t say anything to them. There was no need to. The layout dictated the movement. The placement of the ledges eventually made it apparent where to stand, where to sit and where to skate. Some of the out of town crew were ripping and I enjoyed watching them skate. I found the whole experience pleasant. They pretty quickly were able to figure out the typical movement of the space. And even though they added ten more bodies to our four person session I could still for the most part skate it just like I was before they showed up. A bit of a longer wait in between goes of course but not much. Reggaeton has such good seating/ standing options that not all ten were skating at most times and the same was true for my friends and I. Skate, chill, skate.

I attribute the delay in time it took to adjust to the movement of Reggaeton to the fact that these skaters probably grew up skating skate parks where the layouts motivated everyone to move around chaotically as if they were ants and someone had just kicked their anthill. As humans we tend to be aware of and follow design cues. The design cues of modern skateparks are plentiful and ambiguous.

I saw this same type of thing happen during the recent pandemic when the NYPD was kicking people out of skateparks but they weren’t patrolling basketball courts as much because the parks department had removed the hoops and I guess figured that was enough to keep people out of the courts. So skaters who would normally skate parks started skating basketball court spots like Chauncy. The skaters who would normally frequent skate parks also moved somewhat chaotically at Chauncy before adjusting.

Now let’s compare and contrast these aspects of the ledge court with modern skatepark layouts.

Instead of benches for sitting and standing room on the perimeter of the short ends of modern skateparks we usually find quarterpipes and embankments. The long sides of modern skateparks are sometimes filled with quarterpipes and embankments as well. But they will also have pyramids, ledges, curbs, pump humps ect. abutting the perimeter. The middle of these skateparks are where the main clustering takes place. Ledges are stacked on top of curbs. Embankments are placed behind ledges. Pump humps, pyramids, hubbas, flat bars. As many obstacles as can possibly fit are clustered into these spaces.

Now I’m not saying that this is inherently a bad style of design that should be ditched altogether. I believe it has its place. I’m just taking a closer look at how these layouts function. I don’t expect that anyone will hate their local park after reading this. But I do hope they’ll see it in a different light and in the future be more open minded to different styles of skatepark design.

Skate parks are laid out this way to accommodate as many styles of skating as possible, while also allowing skaters to flow around the park and hit obstacle after obstacle. This inevitably leads to a lot of lines of cross traffic. That in turn leads to competition for space and obstacle use.

The arrows in the picture above represent all the many directions that skaters will move in this park.

Besides the random skatepark images I pulled from the internet I’m going to be using photos I took of the the LES Coleman Skatepark in NYC. I’m using the LES park as an example in this article for multiple reasons. First of all I think LES is a very well designed park. The obstacles are all highly functional dimensions. There’s a nice variety. It has a good flow. I thoroughly enjoy skating there. Except when it’s even slightly crowded. Once more than about ten people are there it can become very difficult to skate many of the obstacles. I’m not saying that this problem is any better or worse at LES than at other skate parks. In my opinion it’s better or about the same. I think the majority of skaters who have been to LES can agree that it’s a great skatepark. So by using LES I’m trying to show that even the most well designed skateparks laid out in this fashion have these same types of problems.

The fact that room for standing isn’t strategically placed where skaters will want to stand in order to skate some of the obstacles is a major factor that leads to competition for space and obstacle usage conflicts. As much as I love the LES park it has a glaring example of this type of problem.

If you want to skate the ledge, the flat bar or the quarterpipe on the other end of the area pictured above but you don’t want to skate the bank to wall first, your best option is to stand at the bottom of the bank to wall. You can almost stand by the bench behind the garbage cans but it’s an awkward carve over to the ledge and the run up is just a bit too short to make it a good choice for people. I’ve never seen anyone do it. Plus if the park is somewhat crowded people are probably sitting there already. If you move further away from the bank to wall you’re still just as much in the way as you were before. So the people standing at the bottom of the bank to wall probably don’t like to stand there but if they want to skate the further wally ledge or flat bar there’s really no other choice. This then puts them in the way of people who want to skate the bank to wall. At this point it’s all perspective on who is in whose way.

Let’s say you show up early to the LES park before anyone else is there. You’re skating the bank to wall then wallying the close ledge and then hitting the flat bar. A group of four other skaters show up and they all just want to skate the ledge near the bank to wall and the one on the other side. Frequently all four of them are lingering at the bottom of the bank to wall. This blocks your line and rightfully so you get annoyed at your fellow skaters for blocking your line. They are probably a bit annoyed at you for busting up their session as well. But where else are they suppose to stand. And how else are you suppose to wallride and then wally unless they move. This is a classic example of what I call an obstacle usage conflict. And it leads to competition for space. I believe it also leads to anti social behavior. Instead of seeing other skaters who show up to the skatepark as potentially like minded people with a similar interest it can lead to looking at them as possible hindrances to your own skating. In this example both parties hindered each others skating simply by skating the way they each prefer. So without even talking to each other a negative feeling is likely to develop on both sides. And that negative feeling is what can lead to anti social sentiments and behavior.

When I first started writing these articles I admittedly tended to blame skatepark designers for theses types of issues. But really the designer is tasked with accommodating all these styles of skating in one space. In order to appease all the different types of skateboarders they have to include all of these obstacles in the same space. In order to do that they have to lay out a park in a way that will inevitably lead to obstacle usage conflicts which then leads to competition for space which then leads to anti social sentiments and behavior. In my opinion it’s impossible to accommodate more than one or two styles of skating in one space without running into this progression of negative outcomes. I already elaborated on how I think this type of park became the main design style used for skateparks in Built Environment Inertia so I won’t re hash it here. But I will say again that what’s needed in the general skate community when it comes to skateparks is a paradigm shift.

On a lighter note let’s explore some possible modifications of the Ledge Court. Instead of two identical ledges one ledge could be shorter. Let’s say 10 or 12 feet long. It could be 10 feet wide and only 12 or 13 inches high. This would then serve as more of an end to end ledge and manual pad. But you would still have the long ledge on the other side. Or one side could be 30 feet long and 5 feet wide but be curb height. Another option would be to have one of the ledges at 12 inches wide but still 30 feet long and 14 inches high. The shallow width of the ledge would make most skaters feel more comfortable attempting tech ledge tricks due to the safety of the backing of the wall. Just like the Reggaeton fence ledge effect I talked about in Dimensions. While the ledge would be too shallow for lipslides and it would be difficult to do noseblunt or blunt slides you would have the ledge on the other side which would accommodate those tricks. Any number of small dimensional modifications similar to these ones mentioned above would add a bit of variance to different Ledge Courts while still keeping the overall functionality in tact.

If the space available for a ledge court is smaller than this footprint the ledges could be shortened. If the space isn’t wide enough for two ledges you could just have one ledge and place the sitting benches opposite of the ledge. Assuming there’s enough width for the benches.

If the space available for the Ledge court is larger I would still keep the ledge court the same size and then use the extra space as a separate zone for a different obstacle(s), depending on how much extra space is available.

Besides shape and dimension the materials, color and texture could vary in each ledge court. If there’s a big enough budget for a ledge court, instead of adding more obstacles the ledges could be granite and the ground could be tightly laid smooth brick. Think of red brick ground and polished grey granite ledges. Both ledges don’t have to be the same material either. So while it is a very basic configuration there’s still plenty of design options to toy around with that would lead to a nice variety amongst different ledge courts without losing the social and spatial benefits of the core layout.

(Continued in Part 3)

Thanks JR. Glad you enjoyed the article.

I have skated Freedom Plaza. I actually had a long conversation recently (right before I put out this article) with a friend who grew up skating Freedom Plaza. I was telling him about what I had written so then we were discussing how the skate traffic generally tends to move in Pulaski. Where the locals sit and post up versus where skaters from out of town might sit and linger. Things like that. I’ve only skated Freedom Plaza twice so it was cool to hear the little intricacies only the locals know.

Have you ever skated Freedom Plaza in DC? this article essentially captures why it's perfect... loved reading it